EVERY LITTLE DETAIL IS CRUCIAL AND IMPORTANT ABOUT THE BOWS FOR VIOLINS, VIOLAS AND CELLOS.

The bow that sets the strings vibrating is almost as complex as the violin itself, and just as important. Originating probably in the Middle East, it consists of a long stick which holds at tension a hank of horsehair. The relationship between this and the archer’s bow is obvious. Viewed under a microscope, the horsehair can be seen to have a serrated edge. It is these teeth that delicately grip the violin strings and cause them to vibrate. The bows used today for the violin family are designed to be very flexible and versatile, enabling the player to extract as much feeling and tone as possible from the instrument. They also allow each string to be individually bowed.

Choosing the right master bow with the optimal characteristics for you!

Most suited bow prices:

When considering the best bow for violin, viola or cello, iit may seem that every fiddle player has a different opinion. Choosing a bow is a very personal decision. Fiddle music is very demanding and a having a responsive bow is a must. I have observed that fiddle players use everything from the most inexpensive bows from € 88 to fine old French bows valued at over € 20,000.

The optimal German master bow for students in terms of value and gain should be between € 1000 to € 3000. Everything above is a investment in antique bow variants. Every bow under € 1000 is most suited for hobbyists mucisians and enthusiasts.

A The type and quality of materials a bow maker chooses for making a bow stick has a tremendous influence on the playing qualities of the bow. While a talented and experienced violin maker can make a fine-sounding violin from less than the best maple and spruce, a bow maker needs the very best materials to make a fine-playing bow. Traditionally, that material has been pernambuco. It has been used almost exclusively by the great makers of the past and is still used by all makers today.

This extraordinary wood comes from only one place, the state of Pernambuco on the central coast of Brazil. It began to be exported to Europe in the 1500s as a dye wood, but in the mid-1700s, French bow makers discovered that it had the ideal characteristics for bows. It is a very dense, hard, somewhat oily wood that is difficult to work, but when finished into bow sticks, it has just the right combination of strength, resilience, responsiveness, and elasticity. These qualities are what make a good bow so helpful in performing complex bow strokes, and no other material does the job as well. A very beautiful wood with a fine grain pattern, pernambuco can range in color from dark chocolate through red-brown, red, and golden orange up to yellow. However, the quality varies and from any pernambuco log, less than ten percent is usable for bows. In recent years, the supply of pernambuco has been decreasing and the government of Brazil has put severe restrictions on its export. Expect prices of €280–€1,200 for commercially-made pernambuco violin bows; bows by contemporary master makers can run more than €3,000.

Carbon made bow for stringed instruments:

One option that is becoming very popular is carbon fiber bows. The advantages to carbon fiber bows are that they are very stable, difficult to break and do not warp. However there are many downsides to carbon bows. A carbon bow will never be able to sound nearly as good as pernambuco master bow. It is also impossible to repair them. Since the material itself is very hard for beginning players such as children and students can only transition to a real wood bow with many difficulties.

Properties of the bow stick:

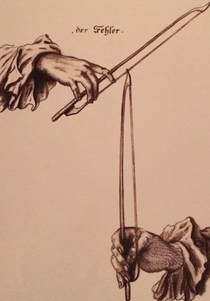

When playing demanding fiddle tunes, a bow with a strong stick may seem to perform best for many players. Keep in mind that the stronger the stick, the less hair tension is needed. Each bow will dictate, depending upon strength of the stick and its camber (the arch in the bow), how tight it needs to be. A common mistake is to tighten the bow so much that it becomes bouncy and hard to control. There is no rule about how tight a bow should be. Again, it depends upon the individual bow and the player's preferences.

Application of too much rosin on your bow:

A common mistake is to put too much rosin on the bow. Many players and teachers feel that they should rosin the bow every time they play. This is not the case. Rosin should be used to help the bow grip the string. If you find a white cloud of it coming off the bow hair when you play, then you are using too much. With rosin, generally less is more. If you feel the hair slipping on the string then apply more of it sparingly until you feel the bow grip the string.

Taking care of your master bow:

It is important to remember to loosen the bow when you are done playing. When tension is left on the hair, it will stretch. Once the hair is too stretched out your bow will no longer tighten. If you can't tighten the bow, don't force it. Take it in to you local luthier for a rehair. Many bows have been damaged by trying to force them to tighten. The other reason for loosening the hair is to let the stick relax back into it's natural cambered shape. If a bow is left tight for too long it will lose its camber and can warp.

Best Wood for making master bows for violin, viola, cello and bass.

For centuries, the finest violin bows have been made from pernambuco trees, which grow in only one place in the world: the coastal region of the Brazilian rain forest.

Pernambuco wood has properties that make it an ideal material for violin, viola or cello master bows. Perhaps most important is its unique combination of strength and flexibility. Its density, which is close to that of ebony, makes it one of the hardest woods in the world. And its flexibility allows it to be shaped with great precision and without cracking or splitting. Amazingly, these bows routinely withstand literally centuries of playing, even though they are tightened and loosened repeatedly and are sometimes subjected to considerable force from the upper arm and hand during playing.

Brazil wood or Pernambuco (Caselpinia echinata) is a rare exotic hardwoodthat is a burnt reddish-orange color. It is noteworthy that Brazil was named after this wood due to the fact that the vivid orange and burnt red colorsof the wood closely resemble thesoil of Brazil.Uses include but are not limited toorange dye, stringed instrument bows, and fine boxes. This is a very stiff wood that is the wood of choice for instrument bows. A glass like finish can be obtained for stunning articles!

Unfortunately, pernambuco is becoming increasingly difficult to obtain because the tree is nearing extinction and has been placed on the list of endangered species. Small amounts are still exported to the Europe, but not every bow maker is able to obtain it.

There are many reasons that the supply has become so limited. One is that, in the past, there were a lot of other uses for pernambuco, from creating dyes to furniture-making. However, bow makers have also participated in causing its scarcity and, aside from destruction of the rain forest in general, are currently its greatest threat. Because violin bows are made to such exacting standards, makers will often go through a lot of wood before settling on a piece that they believe will make a good master bow. The fact that pernambuco tends to be inconsistent also contributes to this problem -- pieces vary widely in density, and entire sections are often thorny or irregular and twisted. In the hands of the less scrupulous or less knowledgeable, it can take as much as ten tons of wood to make a single bow.

The other great threat to pernambuco is the death of the Brazilian rain forest. This is a result of many factors, such as urban development and expansion of roads and infrastructure, the clearing of pastures for raising cattle, and the farming of sugar cane and beans. Many different species of trees are cut down to supply the world with wood or are even burned for charcoal.

So what are contemporary violin bow makers to do? One solution to the shortage is simply to use lesser quality pieces of pernambuco or wood from related species of trees (usually called brazilwood). Because this wood is less dense, the resulting bows often have a larger diameter to reach the standard weight for violin bows of approximately 60 grams and thus look and feel "chunkier." They also often feel soft and must be tightened a lot to provide the player with a comparable feeling of stiffness and resistance. Brazilwood bows are rarely used by professional violinists.

Pernambuco or Caesalpina Echinatais seen as a dwindling resource due to development of the coastal forest regions, and as a result there are long-standing preservation efforts for that tree that have been implemented by both the Brazilian government and various associations of bow makers.

Pernambuco harvesting is now controlled, and the Brazilian government for many years has banned the illegal trade of raw Pernambuco wood, where mass production is so common. Lately this has been more successful due to some new international regulations. All of the regulations on exporting Pernambuco from Brazil apply to limiting the sale of raw wood only, and not to finished bows.

The shortage of pernambuco is also depriving luthiers of the experience necessary to learn their craft. Therefore, the modern bow maker with true expertise is also becoming an endangered species.

Laubach workshop is a contemporary violin bow maker with expertise in selecting pieces of pernambuco that will make good master bows for violin viola or cello. Thus, he causes less of it to be wasted, which helps conserve its limited supply. He is able to determine the likely playing characteristics of an raw piece just by its appearance and feel. His master bows tend to have a slightly reddish appearance, are sometimes flamed, and usually aredark red color. In the hand, they are firm, but supple and draw an even tone without excessive bounce or quiver.Laubach is still able to have enough

high quality pernambuco and is sensitive to the need to conserve it.

How to Care For Your Violin, cello or viola Bow

It is important to develop good habits when caring for your violin, cello or viola bow. A good and responsive bow makes a huge difference in the sound of your instrument. There are several key points to remember to properly maintain your bow. Most importantly, always loosen the hair when you are finished playing. This is done by turning the bow screw counter-clockwise. You should feel the stick relax back into it's original arch (camber). If the bow is left tightened for extended periods, the stick can lose its camber and can even warp. Furthermore, the hair can stretch out. If the hair stretches too much, you will not be able to tighten the bow to playing tension. It is vital to remember never to force a bow to tighten because it is possible to break the butt end of the stick by forcing it. If you can't tighten the hair, you should take it to your violin shop for a possible rehair. Bows should be rehaired depending upon use and the condition of the hair. There isn't one rule about how frequently to have a bow rehaired.

is to remember never to touch the bow horsehair with your fingers!!!

An additional key to caring for your bow is to remember never to touch the horsehair with your fingers, as dirt and oils can get on the hair that will cause it to lose its ability to accept rosin. In general, it is always a good idea to wash your hands before you play your instrument. Some peoples' hands tend to perspire profusely. Not only can the sweat remove the varnish from the stick, iit can also soil the hair at the frog. For those with sweaty hands, frequent hand washing is more than a recommendation -- it is a must. When perspiration builds up around the frog of the bow, it can attract grime that can cause the frog to get stuck in position on the stick. When this happens, the frog will not move -- even when the bow screw is turned to loosen the hair. If this happens, the frog should be taken off of the stick, using care not to allow the hair to become twisted. Then, the stick should be cleaned. If you find that your hand is "eating away" at the stick or the varnish, you can have your luthier apply a long leather to the handle of the stick to protect it. This is frequently done on fine bows to preserve the makers' stamp from wear and tear.

Bow adjustment mechanism for violin viola or cello

The frog glides back and forth on the stick by a simple mechanism of a bow screw and an eyelet. The bow screw is usually made of steel and the eyelet is usually made of brass. The brass eyelet is a much softer metal than the bow screw and can strip. If you find that you cannot tighten or loosen your bow, chances are good that they eyelet has become stripped. On occasion, it is possible to carefully remove the frog from the stick and turn the eyelet one-half of a turn, in order to locate some remaining thread left that has not yet become stripped. Then, it is possible to reset the frog back on the stick and reset the bow screw. This doesn't always work, but it is worth a try.

PROTECTIVE LEATHER AND WINDING FOR VIOLIN OR, VIOLA OR CELLO MASTER BOW

On the stick near the frog is the thumb leather and winding. The thumb leather is there to protect the stick from the thumb and thumb nail. Over time, your thumb nail can wear through the leather and start carving into the stick. If your thumb leather is warn, you should have it replaced at your next rehair. This will help preserve the stick and value of your bow.

head plate for violin, viola and cello master bows

The head of the bow is very fragile and under a lot of tension. At the head, you will find a tip plate. The tip plate can be made of metal, plastic, ivory or mammoth and is there to protect the head of the bow. If your tip plate is not made of metal, it can break when bumped or can crack if the hair isn't carefully inserted during a rehair. If it should crack or break, you should have it replaced immediately.

Using too much rosin is a common mistake made by many VIOLIN OR VIOLA OR CELLO PLAYERS.

Using too much rosin is a common mistake made by many players. Rosin should be applied sparingly and only when needed. You should not see a white cloud of rosin come off the bow when you play. Once there is too much rosin in the hair, it is nearly impossible to get out. When you use too much rosin, it will build up on the strings and your sound can become very scratchy -- since you are essentially playing with rosin on rosin. Also, rosin can build up on your instrument and damage the varnish over time. To avoid this, it is important to wipe off your instrument, strings and bow shaft with a clean soft cloth each time you finish playing. Microfiber cloths work great for this.

Tightening the violin bow too much when you play

Tightening the bow too much when you play is another common mistake. There is no rule for how tight a bow should be as it depends on the strength and camber of the stick and is different for every bow. If your bow is too tight, you will have trouble controlling your bow and it can become too bouncy when an even sound is desired. You can test how tight to make your bow by playing long and even strokes. The hair should just barely clear the stick at the middle of the bow. If you see a big gap between the hair and the stick, then your bow is too tight. You can keep experimenting with hair tension until you find that you have good control over the bow.

When you have develop good habits you will find it very easy to maintain your bow. Eventually, you should be able to do this without even thinking about it.

What's Eating Your Violin Bow Hair? It Might Be Bow Bugs

We've all heard of "Bed Bugs." But did you know there are also "Bow Bugs?" Indeed there are -- little arthropods (related to moths) that live inside your violin case and munch horse hair. How do you know that your case is infested? There are certain tell-tale signs. One is an accelerated rate of horse hair breakage on your bow(s). Another is the appearance of broken bow hairs in a spidery pattern inside your case. You may even see crawling or dead insects, or discover the exoskeletons they leave behind when the molt.

These bugs like to live in the dark. They are most likely to live in cases that are left closed for long periods of time. Because they abhor the light, they are seldom found in cases that are opened frequently. Fortunately, they do not like to eat violins and, aside from destroying horse hair, they are otherwise harmless. However, once they have taken up residence, they are difficult to eliminate and can be transferred from case to case.

How to get rid of them? It is usually a good idea to buy a new case and to re-hair any affected bows. However, if this is not an option, another alternative is to expose the case and bows to sunlight over a period of several days, which should kill the insects. You may also opt to spray the case with moth insecticide. However, you must then keep the violin in a safe place until the chemical dries, to avoid harm to your violin.

For dealing with "Bow Bugs," prevention is the best cure. Try not to allow your case to sit unopened or in storage for long periods of time -- violinists who practice regularly rarely experience this problem.

A Brief History of the Bow

The modern bow is a slender, tapered stick about 28 ¾ inches (73cm) long. It is made of pernambuca wood which has been bent in a dry heat into a gently inward curve. The horsehair is fixed as a flat ribbon in a small hatchet-shaped head at the upper end of the bow and in a movable ‘frog’ at the lower, thicker end. It is this lower end, called the ‘butt’, that is held between the player’s thumb and fingers.

The frog is held in place by an adjustable screw and can be wound sideways, thus tightening the horsehair. If the bow has been correctly designed it preserves its shape under every playing condition, despite the tension. This gives the player a very sensitive control over the kind of tone he produces. The present shape of the bow dates from the end of the 18th century, when it was perfected by the Frenchman Francois Tourte.

Before that date bows usually curved outwards, away from the horsehair, which in practice meant that the player could not exert as great a pressure and generate as decisive and passionate a tone.

The relationship between the various parts of a violin and its bow is an extremely subtle one. Each has a bearing on the others, and developments in one sphere can have striking repercussions on the way the rest behave.

The modern bow and violin, though superficially much the same as their 16th century counterparts, are in fact as different as the music they were each designed to play. Indeed, very few early instruments have survived in their original condition – for to be playable they have had to be modified to suit the new kinds of stress that changing conditions have put upon them.

To get back to the original sound it is necessary not only to make instruments and bows to the original patterns, but also to play them in a way that uses original techniques.

The construction of the bows which are used to play the instruments of the violin family is complex and crucial. If it is not correct, the instrument will not be played to its best advantage, and many subtleties will be lost.

Bows originally curved outwards, but this design was changed towards the end of the 18th century when the Frenchman Francois Tourte produced the shape known today. He was following in the footsteps of many bow makers such as Tartini, Corelli and Viotti. The bows of Cramer have recently been re-examined and have been shown to blend early 18th century features and those of Tourte, the modern bow maker. He designed a slim, tapered stick made of wood, which is bent in dry heat into a slight, inward curve.

A flat ribbon of horsehair is stretched across the length of the bow, from the head to the movable frog at the lower end. Horsehair is used because it has a serrated edge and the teeth vibrate the strings when the bow is drawn across them. The hair is coated in resin to increase this effect. The tension of the horsehair can be adjusted by altering the screw by the frog.

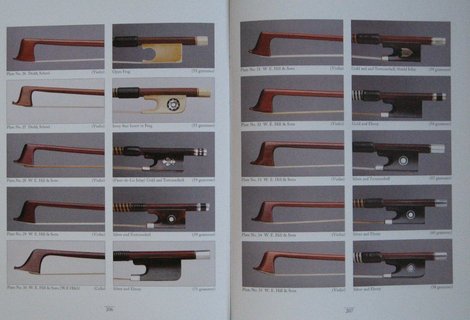

Purchasing Selection of Master Bows for Violin, Viola and Cello.

Could the selection of a violin bow really be as important as the selection of an instrument? In a word, yes. For many people it is also far more of a mystery and therefore more confusing. In this article I will address the importance of a proper bow and discuss condition, playability, sound production, and physical beauty and their relevance as selection criteria. In summary, I will address these factors and how they contribute to the bow's value.

The master bow, because it is very much an extension of the bow arm, is critical to the development of many techniques. It is like the golf club to a golfer, the bat to a baseball player, or the hammer to a skilled carpenter. A bad bow must be overcome, many times by the development of the wrong muscles or the wrong technique in order to make up for its shortcomings. It is for this reason, especially, that the selection of the right bow is especially important to students. A bow does not have to be expensive to be very playable but should nonetheless be well balanced and both strong and supple, and all its parts should fit well and function smoothly. In discussing the various criteria for selection, it is perhaps best to begin with condition.

Purchase conditions of master bows for violin, viola and cello.

Without question, the condition of a bow is critical and must be addressed foremost. When purchasing a bow, before all else one must confirm that the bow has never been broken. Student bows and most lower-cost professional bows lose virtually all of their commercial value once broken, though they may be repaired and used. In general, student bows in any less than excellent condition should be avoided since there are always plenty available in good condition. In studying the condition of a bow, there are many details to consider. See the article titled “Physical Condition of Bows” on page 3 for more information on this topic. Once satisfied as to condition, the playability and sound production of a bow must be considered separately, and it is this two-part process that is often most confusing.

Master bow playability of violin, viola and cello bows.

The playability of a bow is a function of how easy it is to use. It may be considered the tool, and the violin the instrument upon which work is to be performed. Here we must test its balance. Hold the bow in a natural bowhold and see how it feels when moving it through the air. Does it feel comfortable in the hand compared to other bows? Place it on the strings and draw a tone slowly, from frog to tip. Is it easy to control? Does it feel steady and stable, or does it seem to wobble? I recommend starting with just two or three bows in your price range at one time and checking just this much. During this same test, check also for strength. Strength is not a function of how hard or stiff the bow is, but rather how well it holds up as pressure is applied and tone drawn from the instrument. If one bow is less comfortable or harder to control or just feels worse, eliminate it, at least for the moment. Then try one or two more using only this much to eliminate one or two more, keeping only the best feeling ones. Having narrowed your selection to only those which are comfortable and easy to control, you may now consider further criteria.

Sound quality of master bows for violin, viola and cello

At this point, you may wish to go back and compare the remaining bows for sound quality. Here, you are matching the bow to your instrument. A perfectly good bow that sounds good on another master violin may not sound as pleasing on yours, so it is important to use your violin for this test. Some bows will produce a softer, sweeter sound, some a smoother sound, others a grittier or edgier sound. Some will produce a focused, brilliant sound, others a darker sound with more breadth. The finer the bow and instrument, the more pronounced the distinctions will be. Here, too, playing slowly, even just a scale with vibrato, will be sufficient to get a good idea of the sound qualities of the bows you are considering. Eliminate those you don't like.

Response of a master bow for violin, viola and cello.

Finally, you should go back and check another aspect of playability: response. At this point you will be primarily matching the tool to your technique, although, to a certain extent, here, too, there is a match with the instrument. This is where you will want to try any technique such as staccato, flying spiccato, martelé, string crossings, and other such quick-moving techniques which you may wish to employ. It is especially at this stage that you must find the bow which works for you.

In summary, then, I like to use the analogy of trying on shoes. First, the bow must be comfortable to hold and easy to use, much as shoes must be comfortable and wear well. Then, the bow must suit your instrument, bringing out the best in its sound, much like the right pair of shoes may complement the clothes you have already selected to wear. Finally, the bow should be well made and in good condition. Once these conditions have been met, you have found your bow.

Beauty master bow for violin or viola and cello.

While the above listed criteria are the only ones that need be considered with respect to function, you may well find two or more bows suited to your needs and within your budget. At this point, you may wish to select the most beautiful of those that remain. Look at the wood under a good light. Examine the workmanship of all the parts. Select the one which appeals most, but only after all of your other criteria have been met.

Price is very important factor when buying violin, viola and cello bows.

Much as with most other things in life, the challenge is to accomplish this within your budget. Here, a few guidelines may be helpful. I recommend that one restrict the search to bows made of pernambuco wood whenever possible, with perhaps the exception of bows for small children just getting started. For the purposes of this article, I will limit my discussion to master bows priced up to €2,000 and assume that we are talking always of bows in excellent condition. Since the cost of repairing damage to a bow can easily exceed the value of the bow itself, it is essential that the bow's condition be thoroughly examined before making a decision to purchase. This is especially true with student bows, since there are plenty available, and even a few seemingly minor repairs can easily add up to €180 or more. In general, damage to the head or stick of the bow should b e avoided at all costs; a break to the stick on any other than a truly rare bow (otherwise worth many thousands of dollars) will reduce the commercial value of a bow to virtually nothing.

Bows in excellent condition priced between €180 and €1,200 can be generally assumed to be commercial bows (not produced entirely by hand by one individual artist). With these bows, especially, it is best to keep in mind that precious materials used in the frog and adjuster, such as gold, ivory, and tortoiseshell, will usually raise the price significantly and are seldom associated with an accompanying significant improvement in playing qualities. If you are partial to these materials, at the very least you should consider comparing several bows not mounted in these materials (but rather in the more typical ebony and silver) that are selling at a similar price before deciding to purchase.

When searching for bows priced between €300 and €800 (a good price range for beginning and intermediate students), it is probably best to ignore everything but the condition, the wood, and the playability of theviolin or viola and cello bow. Even the names found branded on these bows are of little use as a reference, other than with new bows, since commercial bow companies are forever having bows produced by different groups of people under the same trade name, many times even shifting production from one country to another. Nonetheless, a careful search can uncover some surprisingly nice bows at very reasonable prices. Due to the fact that large numbers of bows are being produced in both China and Brazil and then stamped with various names by commercial concerns there and elsewhere, names are often, though not always, next to meaningless when considering bows in this price range.

One can expect to find more sophisticated playing qualities in bows priced between €1,500 and €3,000. The most frequently encountered bows that represent a good value here were produced in Germany 50 to 100 years ago as commercial bows; it seems that more care was taken in the production, and especially nice wood seems to have been more readily available than is today. I can suggest some names that may be more reliably expected to lead us to some special bows. These brandings include but are not limited to Pfretzschner, Nürnberger, Hermann, Schuster, Hoyer, Rau, Prager, Prell, Knopf, and Bausch. Each of these names represents a well-respected maker, the best of whose work individual work, when available, can be expected to cost upwards of $2,000. However, in each of these cases, the bowmaker has also been responsible for a number of commercial bows of varying quality. The best of these commercial bows are often very fine bows also and can usually be found at prices between €1,200 and €3,000.

The Evolution of the Bow for violin, viola or cello

When was the last time you took a good look at your bow? It’s much more than just a skinny stick you drag across your strings. The bow has a rich history that spans more than 400 years, a history that reveals what a fine work of art and science it has become.

The history of the bow can be divided roughly into three stages of development: the baroque bow, the classical bow and the modern bow.

The Baroque Bow

“Baroque bow” is a generic term for a wide range of early bows used during the baroque period (approx. 1600-1750). It doesn’t describe a specific model or type, as bows of this period were not standardized and every one was different. Baroque bows started out quite short compared to today’s standards, which made them well suited to the rhythmic, non-legato dance music of the time. Early baroque bows also had a removable frog (called a clip-in frog) that tensioned the hair when attached.

As interest grew in cantabile (“songlike”) playing and composers began to call for a smooth, connected notes, the baroque bow grew longer. With this increase in length came changes in construction. A frog with an eyelet and screw gained popularity. The angle of the stick and the head became steeper as the height of the head increased, which allowed a more even and sustained tone across the length of the bow. Probably the most noticeable change, however, was the transition of the stick from convex (curving outward) to slightly concave.

The Classical Bows

The term “classical” (or “transitional”) bow is not quite so broad a term as “baroque”, though it still refers to a variety of bows of the classical era (approx. 1750-1830). Though the changes were not as dramatic as in the baroque era, the popular music of the time prompted modifications to the bow. Structural issues were resolved and design contributions from various bow makers resulted in a stronger bow that could meet the demands of the new, virtuosic music.

Around the turn of the 19th century, the bow’s evolution was largely complete and the era of the modern bow began. A man named François Xavier Tourte is responsible for perfecting the design that has been the standard of bows for the last 200 years. Tourte’s innovations included using premium pernambuco wood and utilizing complex mathematics to define the dimensions of the stick.

The Modern master Bows

The modern bow has changed very little since Tourte perfected his design. The modern bow is the epitome of a versatile tool, as it can play legato passages with evenness and good tone, yet can also perform demanding articulations like spiccato, ricochet and sautillé.

Never forget that bows were created and altered to meet the demands of the current style of music. Though a modern bow will do justice to any style of music, a bow designed in a given era will perform the music of that era with the greatest authenticity. We highly recommend playing music with a period bow if you ever have the chance—it’s an incredible experience!

Looking After Your VIOLIN, VIOLA OR CELLO Bow

This article will be going through some simple steps to looking after your bow for violin, viola or cello. This advice is not difficult to carry out but in the long-run will make sure you get years of enjoyment from your instrument. It also means you will get the best price when selling it.

The violin and accessories are relatively easy to take care of but the bow, more than anything, is the item that is most likely to become damaged if not looked after properly. It is quite a delicate piece of equipment so here are some tips to keeping your bow in great condition.

How To Look After Your Bow

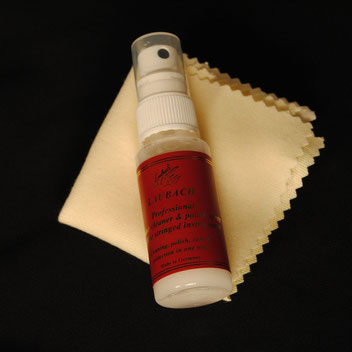

Most of the bow, like the violin itself, is made of varnished pernambico wood. This varnish needs to be kept clean in order to prolong the protective qualities. The rosin on the hairs of the bow will easily stick to the wood and will eventually damage it. Therefore, it is essential to wipe the wood section of the bow with a duster after playing.

If the rosin has become stuck onto the varnish a fully rung out, damp cloth will "Laubach deep cleaner for stringed instruments and bows" remove it. A duster can then be used to polish up the varnish with "Laubach professional varnish cleaner and polish spray". This is also how you would clean rosin from your violin!

The pernambuco wood on the bow is also prone to buckling due to the strain put onto it when the hairs are tightened. To avoid this happening, make sure you do not over-tighten the bow. When looking side-on at the bow there should be a nice arch in the wood bending down towards the hair. If the wood even looks straight, it has been over-tightened and will eventually buckle the wood.

On the same topic, when you have finished playing your violin always unscrew the nut on the bow to slacken the hairs. If the bow is left in the case tightened up, the wood is also likely to buckle over time.

Finally, always be careful when putting your bow away. With the hairs loose, it is very easy to catch them on the holder in the case. This can lead to hairs becoming dislodged from the bow and would then need to be gently pulled out. If this happens a few times it would be necessary to have the bow hair replaced.

I think you will agree that looking after your bow is not difficult. You just need to follow the above steps every time you play and your bow will last for a very long time!